Romantic Rachmaninoff

Romantic Rachmaninoff

Concert Sponsor:

George and Sibilla Boerigter

Sheet music sponsored by a generous gift from the Franklin Kraai Trust.

Program

Saturday, April 26, 2025, 7:30 p.m.

Jack H. Miller Center for Musical Arts, Hope College

Johannes Müller Stosch, Music Director and Conductor

Cameron Renshaw, cello

Finlandia, Op. 26

Jean Sibelius

Kol Nidre

Max Bruch (1838-1920)

Cameron Renshaw, cello

Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

Largo - Allegro moderato

Allegro molto

Adagio

Allegro vivace

Sergei Rachmaninoff's grand Second Symphony is the centerpiece of the concert on Saturday, April 26, 2025, 7:30 p.m. at the Jack H. Miller Center for Musical Arts, Hope College. Johannes Müller Stosch, will conduct the final concert of the 24-25 season. A young cellist, Cameron Renshaw, will perform Max Bruch's emotional Kol Nidre. The concert will open with a piece chosen by the HSO audience. Look for ways to vote in Fall, 2024!

Tickets are $29 for adults and $10 for students through college.

Learn more about the music…

We will be hosting not only the Classical Chat series at Freedom Village, but also Pre-Concert Talks! Details below:

Classical Chats at Freedom Village: These informative and fun talks are led by Johannes Müller-Stosch and take place at 3:00pm on the Thursday before each Classics concert. (Freedom Village, 6th Floor Auditorium, 145 Columbia Ave.)

Pre-Concert Talks: These talks, led by Johannes Müller-Stosch and Amanda Dykhouse, are online under the "Pre-Concert Talk" Tab.

New to the Symphony? Check out the Frequently Asked Question page…

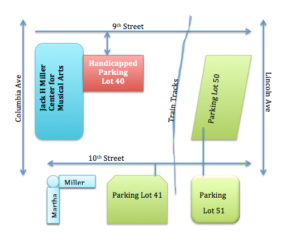

Parking Map at the Miller Center

Holland Symphony Orchestra will reserve and monitor Lot 40 for handicapped parking. The faculty parking lots are available for parking after 5pm

Finlandia, Tone Poem for Orchestra, Op. 26

Jean Sibelius

Born: December 8, 1865, Hämeenlinna, Finland

Died: September 20, 1957, Järvenpää, Finland

Composed: 1899-1900

Approximate length: 8 minutes

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 French horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, triangle), strings

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the people of Finland became increasingly resistant to the oppressive rule of Czarist Russia. Artists and composers such as Sibelius subtly joined this patriotic resistance by nurturing nationalism through their art. For an 1899 festival, Sibelius composed music for a series of tableaux on themes of Finnish historical events. Finlandia, which accompanied the final tableaux, was an instant success, bringing international attention to the composer and the cause of Finnish independence.

From its beginning, Finlandia establishes a mood of defiance with a snarling theme played in the brass. This is answered by an organ-like response in the woodwinds and a prayerful passage in the strings, thought to reflect the earnestness of the Finnish people, even under the stress of national sorrow. Trumpet calls seem designed to appeal to national emotion. The piece closes with a chorale that has become almost a national anthem.

“There is a mistaken impression among the press abroad that my themes are often folk melodies” Sibelius wrote. “So far I have never used a theme that was not of my own invention. Thus the thematic material of Finlandia is entirely my own.” There is good reason for these misconceptions, however; Siblelius’ identification with his people was so complete that even though he did not take his melodies from Finnish folk tunes, many of his melodies, including the chorale from Finlandia, have become folk melodies.

To listen to Finlandia, click here.

Kol Nidre, Op. 47

Max Bruch

Born: January 6, 1836, Cologne

Died: October 2, 1920, Berlin

Composed: 1880

Published: 1881, Berlin

Approximate length: 10 minutes

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 French horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, harp, strings

Max Bruch was a German Romantic composer, violinist, teacher, and conductor. He began composing at an early age and continued to pursue a life of music with a lot of support from his parents and community. He was a well known musical figure during his lifetime though today he is known for only a few works, mostly solos for violin or cello and orchestra. Bruch had a gift for writing captivating melodies. Like many other Romantic composers of his day, he was fascinated by “foreign” music. His Scottish Fantasy was one exploration of music from a different culture. Another one of those pieces is his Kol Nidrei for cello and orchestra.

Bruch wrote Kol Nidrei at the urging of cellist Robert Hausmann, who was envious of the pieces Bruch had written for violin and orchestra. Bruch got the idea to write this piece from a melody given to him by a member of the Stern Choral Society, of which he was director from 1878-1880. The melody was an old Hebrew song of atonement traditionally sung toward the beginning of a worship service on the eve of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. This is the most solemn day of the Jewish calendar and the culmination of the Jewish High Holy Days that begin with Rosh Hashanah. This day is traditionally observed by praying and fasting, and is an opportunity for reflection on the past year, repentance, and setting intentions for the coming year.

Kol Nidrei, an Aramaic phrase meaning “all vows,” is a long, wandering liturgical chant that invites worshippers into this reflective mineset. Bruch treats the traditional, meditative melody with a lot of freedom, breaking it up into groups of three pleading and sorrowful notes, each separated by a musical “sigh.” Eventually Bruch departs from the “Jewish” atmosphere and moves in the direction of German Romantic music, becoming much more flowing in his melodies and even visiting major keys.

Kol Nidre has become one of Bruch’s most beloved and widely performed pieces, and is in the repertoire of every cellist. Bruch became so well known through this piece that the German National Socialist Party assumed he was of Jewish origin when they came to power in the 1930s, and banned all his music. Fortunately the music by this German Lutheran composer survived the ban, and is cherished by soloists and audiences today.

To watch a video of Kol Nidrei, click here.

Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Born: March 20/April 1 1873, Oneg, Russia

Died: March 28, 1943, Beverly Hills, California

Composed: 1906-7

Premiere: January 26, 1908, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Approximate length: 60 minutes

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 French horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum), strings

Rachmaninoff’s second symphony almost never happened! The premiere of his first symphonic work–his first symphony–in 1897 was a disaster. Alexander Glazunov, who was allegedly drunk, conducted a very poor performance of the piece. Critics and the public responded harshly, including composer César Cui, who suggested the piece would only be appreciated by the “inmates” of a conservatory in hell. Rachmaninoff described the experience as “the most agonizing hour of [his] life.” This disaster led to one of the most legendary breakdowns in the history of classical music–a bout of depression and writer’s block that lasted three years. He still performed as a pianist and composed some piano pieces, but threatened never to write again for orchestra.

In 1900 some of his relatives convinced him to seek psychotherapy with Nikolai Dahl, who specialized in hypnosis. (Among other treatment approaches, Dahl had Rachmaninoff repeat to himself that he would write again “with great facility.”) This therapy proved to be highly successful, and Rachmaninoff began to compose again. In 1901 he completed his second piano concerto, his best known piece, and performed as soloist at its celebrated premiere. He was so grateful that he dedicated the piece to Dahl.

In the wake of this success Rachmaninoff quickly became a celebrity and was often recognized and crowded by fans. He longed for a quieter life that would enable him to compose, and he wanted to avoid the growing political turmoil in Russia, so in 1906 he and his family moved to Dresden, a city he had previously visited. There he composed many piano pieces and a symphonic poem. That fall he even found the courage to compose his second symphony, even writing to friends, “I have composed a symphony. It’s true! . . . I finished it a month ago and immediately put it aside. It was a severe worry to me and I’m not going to think about it anymore.” He finished the piece quickly, completing his first draft on New Year’s Day, 1907. He continued to revise it and conducted the premiere himself in St. Petersburg on February 8, 1908. This symphony was received with acclaim and was extremely popular throughout Rachmaninoff’s life and beyond. With this piece Rachmoninoff won his second Glinka Prize.

Rachmaninoff’s second symphony is considered his orchestral masterpiece. In this piece listeners experience a mature Rachmaninoff, who succeeds in expanding everything good about Tchaikovsky and Russian romanticism–orchestral colors, rich harmonies, and heartfelt melodies. His language is unabashedly romantic at a time when his contemporaries were moving beyond tonality. Rachmaninoff’s musical phrases are expansive, surging between tender moments and passionate outbursts. The massive scope of the entire symphony (the violin part is twenty-nine pages!) takes listeners on an incredible musical and emotional journey.

The first movement begins with a quiet and simple melodic fragment in the cellos and basses. Almost every melody in the piece can trace its origin to this brief stepwise theme, which provides a brilliant sense of cohesion to this massive symphony. The lyrical opening leads to a mournful English horn solo before the faster main theme begins. Scurrying triplet motives present a different version of the original theme and foreshadow the final movement. Rachmaninoff’s expansive dialogue invites listeners into a musical exploration of tenderness, pathos, and melancholy, with moments that look toward triumph.

The second movement, a scherzo, is the shortest movement. It feels festive despite its minor key, and starts with bustling and sparkling energy. He provides contrast with a broad secondary theme and a complicated fugue. As the movement progresses, four unison horns play a majestic theme derived from the Dies irae, the ancient chant describing the day of judgment, adding a layer of ominous darkness to the emotional palette of the piece. The movement ends quietly

The third movement is the most quintessentially “Rachmaninoff” movement of the symphony, with its rhapsodic and wandering melodies, rich harmonies, and slowly building climaxes. It opens with a theme for clarinet which is repeated by the strings. Pop singer Eric Carmen used this theme in his song, “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again.” Throughout this movement Rachmaninoff wears his heart on his sleeve as he showcases his gift for taking a simple theme and making it expansive, rich, and heartfelt.

The last movement bursts on the scene with enthusiastic joy. It initially takes the form of a tarantella, with quickly moving triplet figures, but moves on to contrasting musical sections that are boisterous, march-like, and lyrical. Toward the end the Dies irae theme from the scherzo returns as a brass chorale, and a grand romantic theme brings the piece to a close.

To watch a video of Rachmaninoff's second symphony, click here.

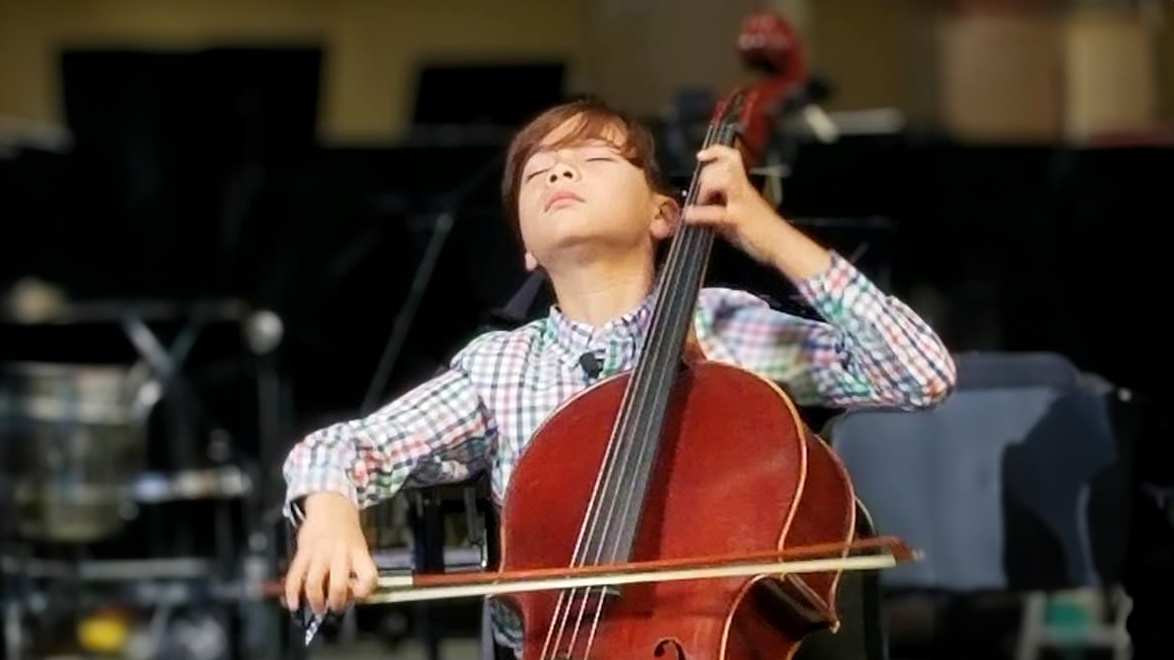

Cameron Renshaw, cello

Rising cellist Cameron Renshaw, age 13, described by NPR as “so exuberant… a born entertainer,” is gaining recognition for expressive performances that are beyond his years. As a first place or grand prize winner of numerous international competitions, including the “First Great Award” at both the Vienna International Music Competition and the Manhattan International Music Competition, he has had the honor of performing in some of the world’s greatest concert halls, such as Carnegie Hall, Mozarteum Salzburg, Lincoln Center, Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, and the Romanian Athenaeum.

Cameron has been featured on local and national media and in a performance on “The Ellen DeGeneres Show” in 2020. He soloed with eight orchestras in the United States and abroad, including his orchestral debut at the age of 8 with the Moscow Symphony Orchestra.

As a From the Top Fellow, Cameron’s performance and interview were featured on the NPR program in March 2024. He was also selected to perform on NPR’s “From the Top: Tiny Desk Concert,” which aired in January 2025. Cameron is looking forward to full solo performances for Young Artist Performances (YAC) in Hilton Head (2025-26 season), as well as the Sobrio Festival in Switzerland (June 2025).

Cameron enjoys playing electric guitar solos on his cello, having performed hits by Metallica and Black Sabbath at Graceland live in Memphis, TN.

Cameron is passionate about promoting music education to the next generation, spreading the joy of music to school kids through outreach efforts and Young People’s Concerts throughout the country. In March 2023, he hosted and performed a benefit concert for his favorite school teacher, Sierra Zylstra, who suffers from Osteosarcoma, to a sold-out crowd at Wealthy Theatre in Grand Rapids.

Cameron takes private lessons at Grand Valley State University and attends University of Michigan Pre-College in Ann Arbor, MI. Cameron has taken cello lessons and masterclasses with esteemed teachers at universities and prestigious summer festivals, including Pablo Mahave-Veglia (long-time teacher), Leo Singer, Richard Aaron, Uri Vardi, Steve Doane, Laurence Lesser, Anthony Elliott, Clara Minhye Kim, Li-Wei Qin, Zvi Plesser, Paul Katz, Wei Yu, Andres Diaz, Lluís Claret, Hans Jørgen Jensen, Tian Bonian, and Julia Lichten.

Outside of music, Cameron enjoys tennis, cooking, and fast rapping.

To watch the pre-concert video, click here.

- This event has passed.

Details

- Date:

- April 26

- Time:

- 7:30 pm - 9:00 pm

- Cost:

- $29

Venue

- Jack H. Miller Center for Musical Arts at Hope College

-

221 Columbia Ave.

Holland,MI49423United States+ Google Map

Organizer

- Holland Symphony Orchestra