Classics III: Beethoven 9 (3:30pm) sponsored by University of Michigan Health-West

Classics III: Beethoven 9 (3:30pm) sponsored by University of Michigan Health-West

Concert Sponsor:

Saturday, April 30, 2022 at 3:30pm & 7:30pm

Concert Hall at the Jack H. Miller Center for Musical Arts, Hope College

Program

Festive Overture, Op. 96

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

1. Allegro ma non troppo; un poco maestoso

2. Molto vivace

3. Adagio molto e cantabile

4. Presto - Allegro assai - Allegro assai vivace

Schyler Sheltrown, soprano

Karen Albert, alto

Jon Lovegrove, tenor

David Grogan, baritone

Choirs of Hope College & Holland Chorale

Text and translation of Schiller's poem, "Ode to Joy": Beethoven-Symphony-No.-9-text-and-translation-PDF

Festive Overture

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born: September 25, 1906, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Died: August 9, 1975, Moscow, USSR

Written: 1954

Premiered: November 6, 1954, Moscow

Approximate duration: 7 minutes

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 3 oboes, 3 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, triangle, strings, and off-stage brass

Like many Soviet composers of his generation, Dmitri Shostakovich spent his career trying to balance the current musical trends, his own creative expression, and the necessity of working within the government’s limits and expressing his country’s revolutionary socialism. This was easy early in his career, when the cultural climate in the Soviet Union was remarkably free; he and other composers could experiment with avant-garde trends, Western influences, and satirical works. Soon the composers’ musical language became too radical; the only acceptable music was a direct, accessible, and popular style. Avant-garde music, jazz, and even Tchaikovsky were banished.

Shostakovich experienced this censure firsthand. When Stalin became angry at what he heard in one of Shostakovich’s operas, Shostakovich and his opera were officially condemned. Later, when the Cold War was raging, Soviet authorities sought to impose a firmer ideological control over cultural expression. At a notorious conference in Moscow, the leading figures of Soviet music, including Shostakovich, were attacked and disgraced. Shostakovich was fired from his teaching positions at the Leningrad and Moscow Conservatories. He was attacked in print, called a “musical charlatan” and criticized for ignoring “the demand of Soviet culture that coarseness and savagery be abolished from every corner of Soviet life.” In the two years following his opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mstensk District, Shostakovich was so sure that he would be exiled to Siberia that he kept a packed suitcase by the door and slept wearing his daytime clothes. He was shunned by society; as an “enemy of the people,” others were afraid to be associated with him.

Shostakovich managed to escape arrest and figured out how to write music that maintained his artistic integrity and pushed up against the limits of what was “acceptable” without crossing the line. He could somehow portray the heaviness of life while maintaining enough ironic humor to suggest lightheartedness. Even though Shostakovich spent his life and career in this delicate balancing act, he seemed to flourish in this tension, writing music that could be received by the authorities and also displayed his fiercely creative thought in challenging and hopeful ways.

Despite the brooding quality of much of Shostakovich’s music, he was also noted for his gregariousness. This quality is evident in his Festive Overture, written in 1954 to commemorate the 37th anniversary of the October Revolution in Russia. After an introduction dominated by the brass, the overture consists of two primary themes: one is fast and brilliant, and the other is optimistic and lyrical.

To listen to the Festive Overture, click here.

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125

Ludwig van Beethoven

Music donated by Teresa Owen

Born: December 17, 1770

Died: March 26, 1827, Vienna

Written: Spring, 1823 - January, 1824

Premiered: May 7, 1824, Kärnthnerthor TheaterVienna

Approximate duration: 65 minutes

Instrumentation: Soprano, alto, tenor, and bass soloists, mixed chorus, piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, and strings

With his ninth symphony, Beethoven expanded the concept of a “symphony” far beyond what it had been in the past and set an intimidatingly high bar for centuries of composers who followed him. Beethoven’s grandest and most influential work was not initially recognized as a landmark, though. In 1822, when he started the work, Beethoven was nearly deaf and had hardly written anything for a decade. The 1824 premiere had been staged to prove that Beethoven could still draw a crowd in Vienna, but he was disappointed by the meager profits and mixed reviews. Beethoven had conducted the work himself, beating his arms and turning pages, but the musicians had been cautioned beforehand to ignore him and instead follow the concertmaster’s beat. When the audience burst into applause Beethoven couldn’t hear it and kept beating; one of the singers had to turn him around for a bow. The second performance was even less successful. The work that Beethoven had written to surpass everything he already had accomplished in the field of the symphony had seemingly failed him. For several years after his death, the ninth symphony was considered too difficult to perform and too long to program easily. Although it won early supporters, it was not established in the repertoire until the middle of the nineteenth century.

The trajectory of Beethoven's masterpiece follows darkness to light, chaos to order, despair to joy. It opens with sound emerging from silence—a poignant gesture from a composer who couldn’t hear what he was writing. The first sixteen measures have no secure sense of key or rhythm. The music gradually builds to a decisive, loud arrival that catapults musicians and listeners into a tumultuous journey. While the overarching structure would have been familiar to Beethoven’s audience, the scale, harmonies, and “perpetual motion” intensity was totally new. The structure of the scherzo is huge, with driving, almost martial rhythms that occasionally give way to lighter moments and anticipation-filled pauses that tease the listener. The light, folk-like trio provides needed contrast. The slow movement alternates between two themes of contrasting key, meter, and mood. They grow ever more fanciful in their decoration until the movement ends peacefully.

After a disruptive chord shatters the peace, a carefully staged drama unfolds. Cellos and basses imitate operatic recitative, the music of the three previous movements is quickly reviewed and dismissed, and a new theme is suggested, which, when it finally takes shape, is a simple song that sounds like a hymn or a folk tune. (Beethoven, in fact, labored painstakingly over this theme.) And then—in a move that must have stunned his first audience—Beethoven welcomes the sound of the human voice into the symphony. The earlier recitative returns and now is sung.

For many years Beethoven had wanted to write music for Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” a glorified drinking song with a strong humanistic message. He toyed with it several times, sketched a number of musical ideas, and even included two lines from Schiller in his opera Fidelio. Beethoven himself wrote the “preface to Schiller’s poem: “oh friends, not these tones… Rather, let us raise our voices more pleasingly, and more joyfully.” When the voices enter, Beethoven’s wonderful melody is finally given words. (In the end, Beethoven used only half of Schiller’s poem, deleting in the process any obvious drinking-song references.) And from there Beethoven creates a totally new symphonic movement, combining elements of symphony and concerto (with a big, virtuosic cadenza for the four soloists), classical variations, Turkish marches (complete with cymbals, triangle, and bass drum), majestic slow meditations, and, finally, a gigantic double fugue.

To listen to Beethoven's Symphony No. 9, click here.

Schyler Sheltrown, soprano

Schyler Sheltrown is a soprano from West Michigan. Heralded as one of “the country’s most vibrant up-and-coming singers” and “a lovely lyric soprano” by the Toledo Blade for her title role in The Ballad of Baby Doe, you have likely heard her in performances across the Great Lakes Region. These performances include the roles of Pamina in The Magic Flute, Musetta in La boheme, Fiordiligi in Cosi fan tutte, Romilda in Serse, Mabel in Pirates of Penzance, The Page in Rigoletto, and Mrs. Hayes in Susannah. She has also performed as the soprano soloist in Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, Mozart’s Requiem, and Debussy’s La damoiselle élue. She also had the pleasure of voicing Joan of Arc as a soprano soloist in Voices of Light with the Rackham Choir at the Detroit Film Theatre. She was a finalist in the Harold Haugh Light Opera Vocal Competition (2017) and, in the same year, lent her talents to The Library of Congress through the Comic Opera Guild for the first recording of The Free Lance by John Philip Sousa. She has received national recognition, gaining an Encouragement Award in the Michigan District of the Metropolitan Opera Council Auditions in 2015 and 2016, First Place in the Scholarship Division of the National Opera Association's solo voice competition (2014), as well as numerous other competitions and prizes.

Miss Sheltrown is a graduate of Michigan State University, where she received her Master of Music (2016) as a Mackey Scholar under the tutelage of Melanie Helton, along with her Bachelor of Music (2014).

Karen Albert, alto

Equally at home on the opera stage and in intimate concert settings, Karen's work covers a variety of disciplines and styles. Recent opera roles include "Katisha" in The Mikado, the dasterdly "Mrs. McClean" in Susannah, and "Cio Cio San's Mother" in Madama Butterfly. Actively pursuing opportunities to share the unique beauty of the art song tradition, Karen has performed works such as Edward Elgar's Sea Pictures and Libby Larsen's Raspberry Island Dreaming. Her love for choral music is evident in her work as well, and she regularly sings both solo and ensemble works with historic Park Church in Grand Rapids, MI and other professional ensembles around the country.

Her scholarship has led to lecture recitals spanning from early French-Canadian folksongs to theological interpretations of Bach arias. Karen has also presented papers at the Midwest Gradatue Music Consortium and at the University of Calgary.

Karen is an adjunct faculty member at Cornerstone University where she teaches music history and vocal technique courses as well as a studio of voice students.

Karen is also the creator of The Barber & The Singer, a lifestyle blog seeking to serve and inspire musicians, artists, and others in the freelance/self-employed community. The Barber & The Singer can be found in the blog section of this website.

Jon Lovegrove, tenor

Tenor Jon Lovegrove has performed with West Michigan Opera Project as Sam in Susannah, as well as with Opera Grand Rapids as 2nd Priest and 2nd Man in Armor in The Magic Flute, the tenor soloist in Rossini’s Stabat Mater, Shem in Noah’s Flood, and Remendado in Carmen. He has also been a member of the OGR chorus since 2007, appearing in multiple productions, including The Mikado, La Traviata, The Marriage of Figaro, and I Dream. Other West Michigan performances have been with GVSU Opera Theatre as Rinuccio in Gianni Schicchi, the Kent Philharmonic Orchestra as Rodolfo in La Bohème, and Timothy in 2nd Act Opera’s production of Help, Help, the Globolinks!

Mr. Lovegrove was a soloist for the Michigan premier of Benjamin Britten’s The World of the Spirit with the Evangelical Choral Society in 2013, and has performed with the ECS on multiple other occasions.

Mr. Lovegrove holds an Associate’s Degree in Vocal Performance from Grand Rapids Community College. While pursuing that degree, he was a member of the Grand Rapids Community College Choir, Madrigal Singers, and Shades of Blue Vocal Jazz Ensemble.

David Grogan, baritone

The American baritone and music pedagogue, David Grogan, holds Bachelor of Music Education and Master of Music degrees from Texas Christian University, where he studied voice with Sheila Allen and pedagogy with Vincent Russo. His love of choral music was solidified under the tutelage of the late Ronald Shirey, who taught Grogan much of his musicality. He earned his Doctor of Musical Arts in Vocal Performance and Pedagogy in 2010 from the University of North Texas, where he studied voice with Jeffrey Snider, pedagogy with Stephen Austin, and worked closely with Lyle Nordstrom in the early music program. Grogan’s dissertation was on the vocal pedagogy of Frederic W. Root, who was an American vocal pedagogue of the 19th century. A shorter version of the dissertation was published in the January 2010 Journal of Singing under the title, “The Roots of American Pedagogy.”

David Grogan joined the faculty at the University of Texas Arlington in the fall of 2009, first as visiting professor and in 2010 as tenure-track Assistant Professor of Voice. In addition to providing private vocal instruction for voice majors, Grogan teaches vocal pedagogy, voice class, and choral methods. His background in choral music education is extensive, including experience directing programs in both private and public schools across the metroplex. As choir director at Dallas Christian School from 1996 to 2000, Grogan increased choir participation from 15 members to 115, and took the choir to one of the first TPSMEA competitions. He has taught voice and served as assistant choral director in some of the most prominent programs in the area, including at Arlington High School under Dinah Menger, and Manor Middle School under Tommy Haygood.

Holland Symphony Orchestra Musicians

Violin 1

Amanda Dykhouse

Sara Good

Katie Bast

Jennifer Tuinenga

Jaclyn Burke

Anna Spix

Josh Zallar

Katie Lefevre

Michelle Kellis

Sheri Dwyer

Alison Sal

Violin 2

Michelle Bessemer

Irina Kagan

Patricia Wunder

Linssey Ma

Ruth Vanden Bos

Becky Dyk

Karen-Jane Henry

Emma Bieniewicz

Ellen Rizner

Susan Formsma

Jay Sheridan

Roger White

Viola

Lauren Garza

David Lee

Kennedy Dixon

Daniel Griswold

Sean Brennan

Jamie Listh

Connie Meekhof

Mary Hofland

Laurie Van Ark

Cello

Pablo Mahave-Veglia

Jacob Resendez

John Reikow

Silvia Sidorane

Dawn Van Ark

Kevin Sweers

Anne Thompson

Matthew Heyboer

Esther Peterson

Alex Bowers

Bass

Marcy Marcelletti

Chuck Page

Sam Dykhouse

Jmar Bongado

Aiden Harmon

Flute

Gabe Southard

Jayne Gort

Gay Landstrom

Oboe

Sarah Southard

Rebecca Williams

Ann Hepfer-Isaacson

Clarinet

Gary June

Lindsey Bos

Bassoon

Cynthia Duda Pant

Laura Diaz

Ruth Wilson

Horn

Greg Bassett

Karin Yamaguchi

Michael Wright

Fred Gordon

Tucker Supplee

Trumpet

Bruce Formsma

Aaron Good

Gregory Alley

Trombone

Paul Wesselink

Philip Mitchell

Adam Graham

Tuba

Brendan Bohnhorst

Timpani

Sue Gainforth

Percussion

Eric Peterson

Shanley Kruizenga

Chris Jones

Rachel Coussens

Holland Chorale

Dr. Patrick Coyle, Artistic Director

Kristin Goodyke, Principal Accompanist

Martin Amon

Kerri Baker

Andrew Broussard

Sarah Brown

Jay Bylsma

Karen Bylsma

Brian Carder

Evan Cuperus

Jill DeVries

Robert Edwards, guest

Jessica Fashun, guest

Vincent Frank, guest

Jay Gainforth

Christopher Grapis

John Griffin

Jeff Helder

Steve Hook

Elizabeth Hudson

Chandra Hronchek

Casey Lampen

Kit Leggett

Jean Lemmenes

Jo Meeuwsen

Janet Morrow

Sverre Olsen

Patricia Easa Persenaire

Mike Pikaart

Andrew Plummer

Shela Ritchie

Amanda Robbert

David Schallert

Ed Schmidt

Jennie Schmidt

Joe Terpstra

Justin VandenBrink

Kent VanTil

Stan Witteveen

Carol Zeh

Spera

Eric D. Reyes, conductor

Bethany Dame, keyboardist

Soprano

Maicee Bishop

Emma Bosch

Caitlyn Brown

Darian Davis

Seanna DeWitt

Elisa Fulper

Aletheia Hoffman

Alli Mitchell

Yessi Moreno

Chloe Roberts

Alto

Lauren Bryan

Ellie Dirkse

Allyson Fennema

Leah Fritts

Emma Hakken

Taylor Hofman

Beata Huntington

Kendall Maes

Natalie Plitt

Lily-Kate Pritchard

Rachel Thomas

Chapel Choir

Eric D. Reyes, conductor

Alex Cross, keyboardist

Soprano

Jane Altevogt

Emma Clark

MJ Cocking

Grace Critchfield

Lottie-Brooke Mims

Chloe Smith

Abby Vonk

Gretchen Woell

Alto

Megan Barta

Katie Donahue

Emlin Munch

Kelli Trudeau

Rebecca Yurschak

Tenor

Eliseo Bustillos

Alex Cross

David Hallock

Lorenzo Lumetta

Bryce Robinson

Wesley Stewart

Spencer Whittington

Bass

Bryce Grover

Christian Lundy

Garett Shrode

Andrew Silagi

Ben Walters

Sawyer Winstead

College Chorus

Eric D. Reyes, Conductor

Alex Cross, Keyboardist

Sopranos

Makenzie Chapman

Carola Dettmar

Natalie Gest

Macy Kerr

Hannah Past

Jennie Judd Reyes

Jennie Staton

Leyang Xu

Altos

Bethany Dame

Katherine Hayduk

Anne Klipp

Allison Male

Margaret Prom

Anna Triezenberg

Beth Vandenbroek

Deb VandenHeuvel

Joanna VandenHeuvel

Angela Wagenveld

Ana Wong

Tenors

Todd Schuiling

Ryan VanDoeselaar

Basses

Gary Bogle

Samuel Grosskreuz

Jim Kleinheksel

Isaac Sandoval

Noah Wohlfert

To listen to the pre-concert video, click here.

Learn more about the music…

We will be hosting not only the Classical Chat series at Freedom Village, but also Pre-Concert Talks! Details below:

Classical Chats at Freedom Village: These informative and fun talks are led by Johannes Müller-Stosch and take place at 3:00pm on the Thursday before each Classics concert. (Freedom Village, 6th Floor Auditorium, 145 Columbia Ave.)

Pre-Concert Talks: These talks, led by Johannes Müller Stosch and Amanda Dykhouse, will be posted online this year, approximately one week before each Classics concert. Look under the "Pre-Concert Talk" tab.

New to the Symphony? Check out the Frequently Asked Question page…

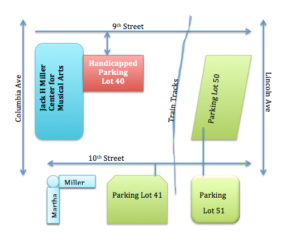

Parking Map at the Miller Center

Holland Symphony Orchestra will reserve and monitor Lot 40 for handicapped parking. The faculty parking lots are available for parking after 5pm

HSO thanks these business partners for their support of this concert!

- This event has passed.

Details

- Date:

- April 30, 2022

- Time:

-

3:30 pm - 5:30 pm

- Cost:

- $22

Venue

- Jack H. Miller Center for Musical Arts at Hope College

-

221 Columbia Ave.

Holland, MI 49423 United States + Google Map

Organizer

- Holland Symphony Orchestra