An American in Paris

An American in Paris

Program

Saturday, September 14, 2024, 7:30 p.m.

Jack H. Miller Center for Musical Arts, Hope College

Johannes Müller Stosch, Music Director and Conductor

Huw Lewis, organ

Idylle (US Premiere)

Joseph Marx (1882-1964)

Toccata Festiva for Organ and Orchestra, Op. 36

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Huw Lewis, Organ

Dances in the Canebrakes

Florence Price (1887-1953)

Nimble Feet

Tropical Noon

Silk Hat and Walking Cane

An American in Paris

George Gershwin (1898-1937)

"An American in Paris," the opening concert of the 24-25 season, will be held Saturday, September 14, 2024, 7:30 p.m. Jack H. Miller Center for Musical Arts, Hope College, Johannes Müller Stosch, Music Director. Huw Lewis, one of our favorite guest artists, will perform Samuel Barber's magnificent Toccata Festiva for Organ and Orchestra. The concert will also feature Florence Price's delightful Dances in the Canebrakes and Josef Marx's Idylle. The evening will conclude with George Gershwin's well-loved An American in Paris.

Tickets are $29 for adults and $10 for students through college.

Learn more about the music…

We will be hosting not only the Classical Chat series at Freedom Village, but also Pre-Concert Talks! Details below:

Classical Chats at Freedom Village: These informative and fun talks are led by Johannes Müller-Stosch and take place at 3:00pm on the Thursday before each Classics concert. (Freedom Village, 6th Floor Auditorium, 145 Columbia Ave.)

Pre-Concert Talks: These talks, led by Johannes Müller-Stosch and Amanda Dykhouse, are online under the "Pre-Concert Talk" Tab.

New to the Symphony? Check out the Frequently Asked Question page…

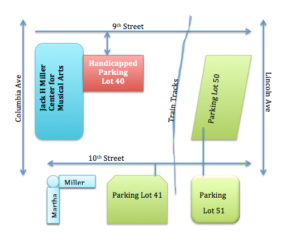

Parking Map at the Miller Center

Holland Symphony Orchestra will reserve and monitor Lot 40 for handicapped parking. The faculty parking lots are available for parking after 5pm

Huw Lewis, Organ

Welsh-born organist Huw Lewis has taught at Hope since 1990. He performs nationally and internationally on a regular basis, and has been featured at important meetings and conventions sponsored by many professional organizations including the American Guild of Organists and the Royal College of Organists.

He was a featured recitalist at the 1987 International Congress of Organists. Dr. Lewis’s playing has been broadcast in America and in Great Britain where he has made numerous recordings for the BBC. He has served on many competition juries, most recently for the 2003 Dallas International Organ Competition.

While a student, Dr. Lewis received numerous prestigious scholarships, fellowships, and prizes. He studied at the Royal College of Music in London, at Cambridge University and at the University of Michigan.

Details

- Date:

- September 14

- Time:

-

7:30 pm

- Cost:

- $29

Venue

- Jack H. Miller Center for Musical Arts at Hope College

-

221 Columbia Ave.

Holland, MI 49423 United States + Google Map

Organizer

- Holland Symphony Orchestra